![_8038907 copy]()

The late-2013 OM-D E-M1 is the successor and upgrade to the very popular early-2012 OM-D E-M5. It’s now clear why the camera was launched with a mouthful of two names: OM-D is a line of products, E-Mx is the model. In this review, we will refer to them as E-M1 and E-M5 respectively to avoid confusion. As you all probably know, I’m very familiar with the E-M5; this camera has served as my travel and teaching camera for the last year, and has now clocked somewhere north of 40,000 exposures (I also reviewed it here). What’s changed in a year? Quite a lot, it seems: certainly enough to get excited about. There’s also a new confirmed lens – the 12-40/2.8 M.Zuiko PRO, available with the camera, and a matching f2.8 telephoto for next year.

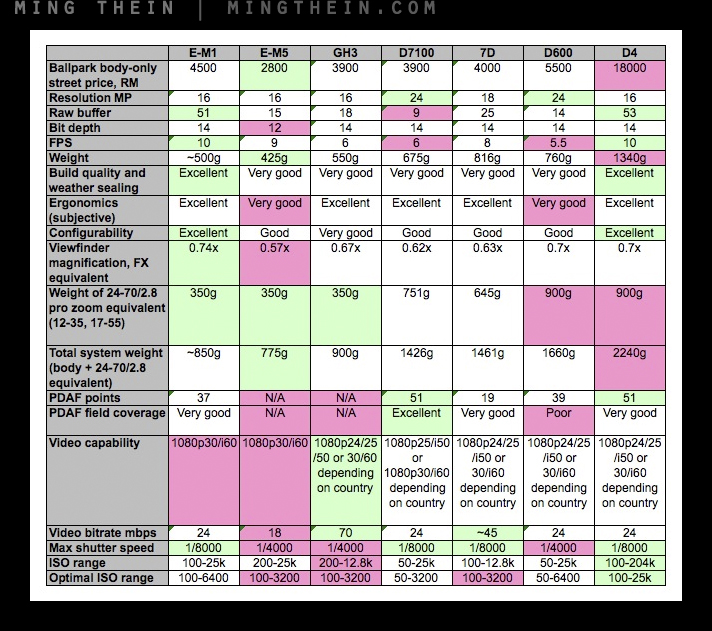

This review will be in three parts for ease of reading (this part is already north of 4,400 words) – the camera itself, today; a relative comparison with two other benchmarks, tomorrow; and a review of one of the two lenses announced with the camera shortly thereafter – the 12-40/2.8 M.Zuiko PRO. A quick note on testing methodology: a range of lenses were used for the review, including the new 12-40, the 50-200/2.8-3.5 SWD for 4/3rds, the 12, 45, 60 and 75mm primes, and the Panasonic 14-42X. You won’t find full size images here due to image theft/ IP issues; go by what I say not what you see – there’s an enormous difference between a small web JPEG that’s been attacked and oversharpened by Flickr’s downsizing algorithm and a full sized one or a RAW file in any case, plus of course the monitor matters. There will be 100% crops where noted, however.

A set of images shot with the E-M1 will be here on my flickr page, and continuously updated as I use the camera more.

![_8038925 copy]()

![_8038931 copy]()

None of the headline spec is a surprise*: all-new Live-MOS 16MP sensor with phase detection AF on chip, a new image processor (TruePic VII), no AA filter, 10fps in AF-S mode, 6.5fps in AF-C tracking mode in conjunction with the PDAF system – and to make the most of that, the buffer is now 40 RAW frames at 10fps, or 51 at 6.5fps; that’s about as good as it gets at any level of product. Upgraded 5-axis system compared to the E-M5′s unit; similarly upgraded robustness and build quality – the entire camera is now magnesium alloy, instead of just the front and top plate. It’s supposedly more water- and dust-proof, in addition to being freeze-proof down to -10C. You’ll also have noticed the new inbuilt grip, which houses the wifi antenna – the camera acquires the remote abilities of the E-P5 (reviewed here) with extended control capabilities. We have a good old-fashioned PC sync port for use with studio strobes, too.

*I am very against leaks and rumours but I mixed up timezones for auto posting this morning (I’m on a location shoot all day) and accidentally posted an hour early. Mea culpa, and my apologies to Olympus and the other media – this was most certainly NOT intentional.

![_5028005 copy]()

I had to test it. You know, waving a red flag at a bull and all that – 10 minutes under a hot shower while powered on, sitting in about 1cm of standing water. All whilst intermittently shooting a frame or two, and no ill effects whatsoever afterwards. Impressive, to say the least.

![IMG_2702b copy]()

![IMG_2703b copy]()

Body-in-white – all magnesium front/back/bottom, compared to just the top and front of the E-M5.

The EVF has been significantly upgraded too; it now uses the same panel from the excellent VF-4, which has near-double the resolution of the E-M5 (2.4m dots vs 1.4m) with dynamic brightness adjustment and much higher magnification. The tilting touch-sensitive LCD remains, but is now in a slightly thicker (and presumably more robust) housing than the E-M5. There’s also one neat electronic feature that stuck with me: the slightly confusingly-named color creator tool. On top of that, we have a new video algorithm with higher bitrate – 24mbps vs 18mbps – though still unfortunately 30p/60i not 25p/50i, and a standard 3.5mm mic-in port. On top of all of this, there are even more customisation options and extra function buttons than before.

![_ET30101b copy]()

Let’s start with the important stuff: we now have phase detection AF capability on the sensor. In real terms, this means both much faster subject acquisition and the ability to track moving objects; in practice, the difference is quite noticeable. The camera is much more positive with acquiring and locking on to moving subjects, and the little ‘CDAF-jitter’ where the lens racks back and forth on the target to adjust for small changes in subject distance is mostly gone. There is a catch, though – the phase detect photosites don’t occupy the entire imaging sensor; instead they’re a diamond-shaped array of 37 points that cover a good portion of it; comparable to the best of the DX cameras, and much better than the full-frame ones. I’m told that the layout of the PDAF photosites was designed to minimize imaging data loss; instead of losing an entire line or or alternate pixel to AF, we have a diagonal grid array somewhat reminiscent of the Fuji SuperCCD which replaces a alternate green pixel on every alternate row. This allows the imaging data from that pixel to be interpolated from quite a number of neighbours. In practice, there is almost no noticeable degradation – you have to be shooting subjects with very high frequency detail at optimal resolving power to even suspect that something might be amiss.

**If you’re wondering about the lack of action photos in this review, it’s because the weather has been pretty bad during the testing period – I tracked some unexciting motorcycles and cars, but didn’t produce anything of visual interest whatsoever. In any case, given the popularity of the trees photoessay, I felt that perhaps a different subject to the usual urban/ street documentary might be welcome for this review; no doubt you’ll be seeing plenty of this style of image from me in future.

![_ET30292b copy]()

With dedicated M4/3 lenses, the system still uses CDAF most of the time; it’s not until things start moving and you switch over to C-AF that the PDAF system takes over. It also appears that the camera now gets flummoxed far less by very bright point sources (blown = no contrast = no focus) – situations that left the E-M5 hunting will result in a jitter but eventual lock on the E-M1; presumably it’s switching over the the PDAF system here. It’s worth noting that the camera obviously tracks much better if your subjects stay within the PDAF area; outside that, behaviour reverts to conventional CDAF – which is to say, not very useful for continuously moving targets. (That said, it’s still better than a DSLR – once you exit the AF grid, you have no AF ability whatsoever.) However, with legacy 4/3 glass, the camera is always in PDAF mode; you can tell based on which AF grid option you’ve got displayed – the brackets or diamond shape is PDAF.

![_ET30177b copy]()

There’s also the ability to add AF fine tune compensation for individual lenses, too. I had the opportunity to try an E-5 (itself no slouch at AF speeds) side by side against the E-M5 with the same lenses: I don’t see any difference in focusing speeds or ability to jump quickly and decisively to different subject distances. This is a huge bonus for legacy 4/3 system users: all your glass is now usable at normal speed again, and the new body is both more capable and smaller than the outgoing one. For M4/3 users, there may not be quite so much excitement about use of 4/3 lenses – until you start looking for high grade special purpose glass like the 50-200 SWD, 150/2, or the 90-250/2.8…

![_ET30316b copy]()

Bottom line: “are we there yet” for mirrorless AF? I’d say nearly. C-AF isn’t as positive or snappy as the current generation (say D3/D4) but it’s certainly usable with care; about on par with the D200 generation, I’d say. We need one more round of iteration (or a judicious firmware update). The E-M5 was already at the cutting edge for single-AF speeds; the E-M1 is slightly faster there, and can now reliably track moving objects, too.

![_ET30302b copy]()

Let’s talk about ergonomics, haptics and the all-important build-feel. First, bad news: the camera has definitely gotten bigger. Wider by about 1cm or thereabouts; height remains the same. Depth obviously increases because of the grip. Adding the vertical portion of the battery grip increases size significantly; the grip itself is twice the height of the E-M5′s unit. There’s also a new one-piece vertical grip (HLD-7); it’s deeper and taller than the E-M5′s unit, making the whole combination a bit bigger, but the ergonomics better. Having found the most comfortable setup for the E-M5 to be with the grip extension piece only, changing batteries annoyed me because this had to be removed before accessing the compartment in the camera; fortunately we can now shoot the naked E-M1 and change batteries easily without having to do this. I don’t have a D7100 or GH3 handy to compare, but I’d say the size is not far off either of these cameras now (also gripped-up, of course). Ergonomics are excellent either way, but I’m personally lamenting the fact that the camera is not ‘really small’ anymore but just ‘small’ – those of you with bags that fit perfectly may need to rethink your packing solutions.

![_ET30288b copy]()

The body is now all-magnesium instead of just top and front plates; it’s slightly heavier, but not by much. The increased surface area has made for some welcome changes to ergonomics though – there’s now space for additional buttons, as well as an increase in size of the old ones. We get a dedicated drive mode/ HDR/ bracketing and AF mode/ metering buttons; the same two-position switch to control dial and button function (both positions being customizable, of course) a-la E-P5; the much-maligned top plate play and Fn1 buttons are now relocated and much larger (though I personally liked having those buttons next to each other because it made for easy review-zoom); the mode dial locks, and the power switch has now moved to the top left corner. The exposure mode dial is now on the right, easily accessible with your right thumb and forefinger. It also has a locking button to prevent accidental rotation. What I don’t understand is the choice of ‘auto’, ‘photo story’, ‘art’ and ‘scene’ modes on the dial – this is billed as being a professional camera. Surely Olympus could put all of the hipstagram faff onto one position and given us a couple of quick-access customizable slots? A shame, if you ask me; time for the black marker…

![_ET30084 copy]()

SOOC JPEG.

![_ET30084b copy]()

My conversion from a color version; I’d say the camera’s native interpretation is pretty darn good.

There are two new shortcut buttons in front by the lens mount, too. It’s ergonomically better, but we can’t do single-hand power on-s anymore. In a final minor change, the control dials are angled and further apart – not that there was anything really wrong with the old ones. All in all though, I think the changes are positive: the camera really feels like a solid little brick in your hands, in a good way. This is a piece of equipment that says ‘professional use’- right down to the same spatter-finish magnesium paint as the single digit Nikons and Canons. The strap lugs are still unfortunately the D-ring type: whilst they don’t munch your hands like the OM-D and E-P5′s rings do, they transmit unnecessary amounts of noise to the body when recording video; I’d still prefer to have built in metal loops like the Canons.

![_ET30230 copy]()

Another SOOC JPEG/ own conversion pair – bit more of a difference this time because I could selectively darken the green foliage…

![_ET30226b copy]()

I’d always thought the EVF in the E-M5 was one of the better ones; until I used the VF-4 during the E-P5 review period. The E-M1′s EVF goes a step further: taking the same 2.4m dot panel, we now have dynamic brightness control which is supposed to render high contrast, bright and dark scenes with more natural-looking dynamic range. Whatever they’ve done, it seems to work. Whilst an EVF still cannot match a good optical finder on dynamic range, we’re getting ever closer with each iteration. On the colour, tonality and detail front – this is a notch above the previous model. And you can still adjust the color temperature of both EVF and LCD, which is a nice touch.

![_ET30195 copy]()

SOOC or DIY conversion? If you’d guessed SOOC, you’d be right. I’m impressed.

![_ET30193b copy]()

My conversion from color.

In a recent article on the future of the DSLR, one of the sticking points was viewfinder technology: I think those arguments are losing weight with every generation of EVF. The E-M1′s panel is now about the same size and magnification as the D800E; something impossible to do with a smaller sensor size simply because of the laws of physics – you’d land up sacrificing brightness or size since you have to make a smaller image area larger. On top of that, we of course have the ability to a) see actual depth of field* all the time, b) have dynamic information overlays, c) judge exposure and d) judge color. There’s a new tool called the Color Creator which takes advantage of this: effectively, it’s a live dynamic white balance and saturation shift; in conjunction with the live tone adjustments – effectively curves – you have an enormous and instantly visible ability to alter color balance to taste on the fly, just using the front and rear dials. It also allows you to apply color filter effects to B&W conversions – e.g. darkening blue skies with a red filter – by reducing saturation to zero and shifting the hue. In fact, with the quality of the new jpeg engine, it’s even one less reason to shoot RAW for most people.

![_5028010 copy]()

Screenshot of the color creator; normally there’s a live preview of the effects on the image underneath with the wheel overlaid on top, but it’s easier to see on a black background in a still. This overlay can be programmed onto any one of the OM-D’s many, many shortcut keys.

![_ET30260b copy]()

*No SLR viewfinder shows actual depth of field; most of the time you’ll preview at around f4, or perhaps f2-2.8 if you’re using a dedicated manual-focus camera. Try it if you don’t believe me: notice how brightness of the finder and what’s in focus does not change much between f1.4 and f2.8 when using DOF preview. Sadly, focusing snap/ precision with fast lenses has been long sacrificed for brightness since the era of slow consumer zooms. There are few really good viewfinders out there now; even the ‘pro grade’ cameras are nowhere near as good as those of the film era.

![_ET30309b copy]()

One of the key strengths of the E-M5 was its stabilizer – those of you who’ve been reading the site for some time will recall that I was not a big fan of the earlier incarnations in the E-PM1, E-PM2 and E-PL5; those were prone to creating a double image under certain conditions. The E-M5′s 5-axis stabilizer is the only one I think is good enough to match and even surpass lens-based IS systems. The E-M1 is equipped with an upgraded version of this, supposedly good for an additional stop – Olympus internally claims 5 stops vs 4 stops, most of the gains being visible at slower shutter speeds. I found in practice that the E-M1 was a bit better, but it’s tricky to quantify exactly how much better. Suffice to say that I think it’s still the best a) handheld video platform and b) manual focus platform for this reason. (Caveat: I have not used the GX7 and its sensor-stabilizer yet.) It’s therefore a shame that the auto-ISO implementation picks a rather high shutter speed by default – and you have no way of overriding this and setting your own minimum (multiples of 1/FL equivalent would be ideal); this means you land up using a higher ISO than you might otherwise be able to get away with, using the full capabilities of the stabilizer.

![_ET30077b copy]()

SOOC JPEG – beautifully rich, accurate color.

The shutter unit itself is different: it’s based off the E-P5′s design, now reaches 10fps, has a higher 1/8000s maximum mechanical speed, and unfortunately isn’t as quiet as the E-M5 – the pitch seems to be a bit higher (it’s a ‘click!’ rather than a ‘thut’) probably because the blades have to move quite a bit faster to hit 1/8000s. That said, though overall volume/ vibration levels are about the same.

I’ve been shooting more and more video of late, both in conjunction with the workshop videos and creative direction work for clients; I’ll usually operate the second camera for pickups, run and gun etc. The E-M5 has been my choice for its stabiliser; I know of at least one local production house that’s seriously evaluating these cameras to add to their arsenal. The E-M1 is even better because we now have a dedicated MIC-IN port, higher data rate (24mbps vs 18mbps) and a new algorithm that reduces block noise in areas of gentle gradients/ solid colors, like skies. Unfortunately, we cannot choose frame rates: it’s 1080 30p/60i only; 1080p50 would be nice. Now for some good news: rolling shutter artefacts are almost entirely absent, and even though it shoots 30p/60i, we don’t have any nasty artefacts from artificial light sources – the flicker reduction system is quite effective.

![12-40 comparison corner CA flare]()

Note complete lack of CA. 100% crops are here.

Olympus has implemented a new processing engine in the E-M1 called TruePicVII. Whatever the name, the processor does a few important things: corrects for CA and lens distortion based on profiles generated for individual lenses (unfortunately only Olympus 4/3 and M4/3 lenses at the moment, much like how Panasonic only offers in-body correction for its own lenses) and dynamic sharpening depending on lens’ resolving power to avoid oversharpening haloes. For the most part, it works; though there were a few instances with certain lenses where there was a bit too much CA for the system to remove. The processing algorithms apply only to JPEGs, though they can be retroactively applied to the RAW files too if you choose to use the Olympus raw converter. Sadly, I still firmly believe that none of the camera makers’ software can match the flexibility of the Photoshop suite; they should really just focus on building cameras and leave software to somebody else. Though the new imaging engine only works on SOOC JPEGs, though the effect is really quite noticeable – between this processor and the other hardware improvements on the sensor, images just have a bit more ‘bite’ than the E-M5 – which we shall see in part two tomorrow.

![E-M1 JPG ISO series]()

ISO series – SOOC JPEG, NR off. 100% crops are here.

Good news: this camera produces the best SOOC JPEGs I’ve ever seen; the output is very similar to the E-P5 (which you’ll recall I was very impressed with), but with the added flexibility of the color creator to shift WB and saturation (or apply virtual filters to your B&Ws). Sharpening is sensitive and not overdone; detail is crisp and the microcontrast characteristics of the lens are preserved well. The sensor’s overall tonal response seem quite similar to the E-M5; however there’s about a stop more dynamic range in the shadows, and noise seems better controlled – somewhere between half a stop to a stop. I’d say ISO 3200 still delivers good quality, and ISO 6400 is usable – this with JPEG noise reduction off. More importantly though, there’s little chroma noise and almost no odd hue shifts in the shadows at higher sensitivities caused by amplifying different color channels unequally. Color has always been Olympus’ strong trait; no exception here. Auto white balance is better than ever; it seems to have a slightly wider operating range specifically lower down in the Kelvin scale, making it able to better accommodate incandescent sources. The majority of the JPEGs in this review are straight out of camera; there are a few examples where I’ve processed a color file to compare against a SOOC B&W, and I think you’ll probably agree that the results are actually surprisingly close.

![_ET30089b copy]()

ISO 6400 SOOC JPEG. A good amount of the red channel info is retained, and there’s remarkably little chroma noise or odd hue shifts.

Bad news, though: given that I was unable to run the raw files through my preferred ACR workflow (there’s obviously no ACR support at the moment), this portion on image quality is therefore based of JPEG output and is preliminary – I will update this later as soon as Adobe releases an update for the E-M1. Honestly, given what this camera can do in JPEG mode, I’m very much looking forward to seeing just how much latitude lies in the raw files. Bottom line: sensor technology has evolved significantly; the previous generation of 16MP cameras had more than enough image quality for most uses; any improvements on that are of course welcome, but are not game changing.

![_ET30123b copy]()

A quick note on battery life: the E-M1 uses the same batteries as the E-M5 (good news, you won’t have to buy new spares). I averaged about 500 frames per charge, which is about 20-25% less than the E-M5, though it’s worth noting that I was always using a mix of 4/3 and M4/3 glass; I suspect the 4/3 glass is significantly more power hungry as there are larger motors moving heavier elements around. You’d probably get better battery life using native M4/3 glass exclusively – I’ve recorded up to 2,300 images on one battery (!) with the E-M5 in the past – shooting normally, long exposures, a decent amount of chimping etc.

![_ET30059b copy]()

On the subject of use with legacy 4/3 lenses: I get the impression that the camera was developed with these users in mind; it’s been a long, long time since the last proper update to the proper 4/3rds line (I’ve been assured this isn’t dead, and an E-7 is in the works – update: my misunderstanding of the material presented. There was an E-7 design study, which may or may not happen.). The camera itself is physically a bit larger; larger than it needs to be to fit all of the (enlarged) buttons in, but at the same time quite similar in size to the earlier E-420 and E-520 cameras. The obvious question of whether legacy glass makes sense: for existing 4/3 system owners looking for an upgrade, there’s no question that the E-M1 is quite a few notches ahead of the E-5. For M4/3 owners, there are certain special purpose lenses that are available for 4/3 (and M4/3 with the adaptor) that might be of interest – specifically the pro telephotos – 55-200/2.8-3.5 SWD, the 150/2, the 90-250/2.8 and 300/2.8 – that aren’t available for M4/3. Performance of these lenses remains excellent on M4/3; this review was shot with a mixture of native M4/3 and 4/3 glass. Using the normal range zooms with an adaptor doesn’t make a lot of sense – native mount options are available and physically smaller.

![_ET30047b copy]()

Time to wrap up. The OM-D has matured. It’s no longer a ‘cute’ but serious camera; it’s now matured and grown into a even more of a workhorse. It’s no longer small; in fact, it’s similarly sized to my F2 Titan (which is of course full frame). The upshot is that the camera balances much better with the larger 4/3 lenses, especially with the vertical grip attached; but it’s also ergonomically a bit more comfortable especially for people with larger hands – a kind of Goldilocks. This is a complex camera; one that will take time to master and even just to work out the optimum configuration for – and I plan to post an update in due course after a bit of time shooting with it properly, and once ACR supports its raw files.

One note on price – at $1399 for the body, it’s a lot higher than the E-M5 was, dangerously into high-end APSC territory. No question: I think it’ll be the biggest stumbling block to this camera’s success. The inclusion of amateur modes on the mode dial makes me question the target audience somewhat – I think the camera should have been a no-compromises tool either way, and for the most part, they’ve succeeded. Price is one of the things I hit the GH3 for; it had pro aspirations and pro pricing, but fell a bit short in several areas like size and viewfinder quality – though it makes for an very good specialized video tool. As we’ll see tomorrow in part two, there’s no real direct competition – it’s tough to figure out what the relative value/ pricing should be. At least a bit of the grip you had to previously buy with the E-M5 is now included…

![_ET30074b copy]()

If you’ve come away from this review thinking I’m feeling pretty positive, that’s because I am; aside from the inclusion of PDAF on sensor, the other upgrades are evolutionary (but welcome) rather than revolutionary. In many ways, the E-M1 feels like the next logical step in the evolution of the camera: we are now seeing the best of DSLR (PDAF, ergonomics, comprehensive system) and mirrorless (CDAF, excellent and realistic EVF previews, 5-axis stabiliser, smaller physical size) finally coming together into one package. Perhaps the whole review is best summed up as this: you’ll know that I simply don’t have the time to review things that aren’t interesting or relevant for my personal or commercial work; however, on the basis of my evaluation over the last week, I’ve ordered a pair of E-M1s – one for set up for stills, and one for video work. MT

The Olympus OM-D E-M1 is available for preorder here from B&H and Amazon.

The Olympus 12-40/2.8 PRO is available for preorder here from B&H and Amazon.

Finally, a big thank you to Olympus Malaysia for the loan and advance preview of the camera. They are also running a touch and try launch event for users on 21/22 September – I will be in Europe unfortunately – but you can register here. The camera itself is available for preorder directly here; I’m told that worldwide public availability is set for end of October.

_____________________________

Enter the 2013 Maybank Photo Awards here – there’s US$35,000 worth of prizes up for grabs, it’s open to all ASEAN residents, and I’m the head judge! Entries close 31 October 2013.

____________

Visit the Teaching Store to up your photographic game – including workshop and Photoshop Workflow videos and the customized Email School of Photography; or go mobile with the Photography Compendium for iPad. You can also get your gear from B&H and Amazon. Prices are the same as normal, however a small portion of your purchase value is referred back to me. Thanks!

Don’t forget to like us on Facebook and join the reader Flickr group!

![appstorebadge]()

Images and content copyright Ming Thein | mingthein.com 2012 onwards. All rights reserved

Filed under:

Gearhead: Reviews ![]()

![]()